Carving a Legacy

So few of us today actually make anything with our hands. Our daily efforts culminate in the creation of memos, reports and spreadsheets. But not so for Ian '03 and Colin McNair '08, whose craftsmanship renders practical works of art.

Written by Jason Ryan • Photography by Gately Williams

You would think he was carving butter.

Again and again, Ian McNair '03 draws a sharp tool across a block of cedar, peeling back layers of grain. Minutes ago, the cedar resembled a chunky football. Now it's a duck. McNair's carving looks effortless, easy, as if the cedar gives no more resistance than would a bar of soap.

It is not effortless and easy. When an amateur attempts to pare down the cedar with McNair's spokeshave, the blade jumps and bumps erratically across the wood, nicking and gouging what had previously resembled a duck. The amateur adjusts the angle of attack, but this results in even deeper gouges. In the next attempt, the tool skips across the surface with all the grace of a rusty razor blade being dragged across a cinder block.

It's some comfort that McNair carves wood for a living. Also comforting is the fact that he and his brother, Colin '08, have benefited from a lifetime of tutelage from their father, Mark McNair, a preeminent American woodworker. Simply put, the McNair boys have enjoyed a lifetime of learning from the best.

The McNairs carve decoys. They typically carve duck decoys, but other wildfowl as well. Once upon a time, wooden duck decoys were critical equipment for American hunters. Placed in water, the decoys lured live ducks flying overhead, fooling the animals into believing a safe habitat awaited them below.

Hunters still use decoys, though today's decoys are usually mass-produced and made of plastic. Wooden, handmade decoys have gone the way of the dodo bird, at least for all but the most eccentric sportsmen. If you encounter a wooden decoy nowadays, chances are you're standing before a mantel, not wading in a pond. Wooden duck decoys have become objets d'art, valued much more for their beauty and craftsmanship than for any ability to attract live specimens. This evolution matters little to the McNairs, who carve decoys that can perform in any environment. Their birds always look pretty gosh darn good, whether being eyed by man or mallard.

In the Sticks

No matter how you map it, it's a hike to reach the McNair homestead. The family's old house overlooks a creek on the bay side of Virginia's remote Eastern Shore. The Shore is a narrow peninsula that divides the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. To reach it from the south, one must cross a 17-mile-long bridge that connects the tip of Virginia's Eastern Shore with Virginia Beach and the nearby port city of Norfolk.

It's not until you've started across that seemingly unending trestled roadway and left behind the sprawl, the beach hotels and the area's many military bases that you truly feel yourself pulling away to somewhere different, somewhere spared. With the Hampton Roads metro area in your rearview mirror, you glide over the wide mouth of the Chesapeake, entranced by the staggered streetlights that loom for miles in front of you along the bridge. You pass them one at a time, first on the right, then on the left, then back on the right, and so on.

The alternating streetlights, the seams on the bridge that thump regularly beneath rolling tires, the long line of hundreds, if not thousands, of piles that spring from the water to support the bridge — all contribute to form a rhythm, part auditory and part visual. The rhythm draws you out of your roadtripping daydreams and demands you pay attention. You understand the bridge is taking you away. You are being transported. You are being delivered somewhere else.

It's not just a bridge, but the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. In two places the bridge slopes down beneath the water for a mile at a time, the submerged automobile tunnels allowing for ships to pass above. When the bridge-tunnel opened in 1964, it was celebrated as an engineering marvel. Today it remains an impressive oddity, and serves as your last distraction before entering Virginia's Eastern Shore. From there on it is farmland, uncrowded highway, a few small, depressed towns and not much else. It's pretty, but also empty. Good luck finding a decent place to get a drink.

"We're a lot like Cape Cod," says Colin McNair, "but what we don't have is money or popularity."

That's not a complaint. Cash and crowds might spoil the Shore, and the McNairs are sensitive to affronts to the Chesapeake. They like it quiet here. They like it pristine.

Mark and Martha McNair have lived in their home in Craddockville, Va., since the early 1980s. They raised their daughter Delana and two boys here, with Martha homeschooling the kids in the family's dining room. Each morning began with a Bible reading. Then came lessons. Then freedom.

The McNair children enjoyed free rein of the homestead, playing in and across gardens, fields, forests and creeks. For the McNair kids, and the boys especially, it was a natural playground complete with their own small, private island. Boating, fishing and hunting filled their days, the natural landscape making an indelible impression on their young minds. This watery and wooded paradise was theirs to enjoy, and mostly theirs alone.

Paying a visit to their childhood home in November, Ian and Colin McNair took advantage of warm weather to cruise the Chesapeake on the family motorboat. The brothers were pleased by what they saw. They rejoiced at the resurgence of underwater grasses in the bay's shallow creeks, knowing the aquatic vegetation helps filter the water and provides habitat.

They delighted in spying a peregrine falcon, and squinted their eyes to make out other birds flying in the distance. The McNair men, both father and sons, observe birds a great deal. And when the McNairs are not watching birds, chances are birds are being discussed, or replicated.

The Real Duck Dynasty

In the age of the iPhone and all things digital, it is a privilege to make a living by using one's hands. A hard-earned privilege, no doubt, but a privilege nonetheless. That all three McNair men have established careers through duck decoys is a testament to their talent and tenacity.

Mark McNair first started carving as a young man in the 1970s. The son of a Connecticut carpenter and a former student at the Rhode Island School of Design, McNair had become passionate about folk art. In particular, classic duck decoys and other bird sculptures fascinated him. Through much study and handling, he discerned similarities between these carvings and more ancient forms, such as Cycladic figurines made thousands of years ago in the Greek isles. To McNair, the designs of decoys seemed timeless.

Many early decoys were crudely constructed. Yet trial and error revealed that the more realistic decoys looked, the better they typically performed. In the early 1800s, artisans in the United States began making wooden decoys that were finely carved and painted — more or less the closest representations of live ducks that combinations of wood, glue and paint would allow. A new American folk art tradition had unwittingly been born, as carvers were unaware of the significance and value some of their decoys would eventually come to possess. These early American decoys were first and foremost hunting aids.

By the late 19th century, duck decoys began to be mass-produced. During the mid-20th century, plastic versions began to be manufactured, too. Though not as attractive as their wooden counterparts, plastic duck decoys are cheaper, durable and lightweight, making them a practical choice for most hunters. Accordingly, handmade wooden decoys have mostly become pieces of art relegated to a lucrative collectors' market. It's this market that enables the McNairs' professional ambitions.

Mark McNair is renowned among decoy makers and collectors. Few, if any, living decoy carvers are listed more regularly in auction catalogs, says Burton E. Moore III, owner of The Audubon Gallery in Charleston. McNair's carvings are in such demand that he rarely takes commissions for his work and instead carves according to his whims. His decoys and other carvings regularly sell for thousands of dollars apiece. At one auction in 2009, for example, a rig of five golden plovers made by McNair sold for more than $37,000, and two McNair swans now on display at Vermont's Shelburne Museum were purchased for more than $27,000.

"Even old, antique decoy collectors who swear off all living artists have a couple of Mark's just because they're so good," says Moore.

Since 2007, The Audubon Gallery has hosted a one-man, annual winter show of McNair's work. Normally, says Moore, more than half of McNair's decoys are purchased before the show even opens and the birds are put on display. In February, the King Street gallery updated tradition and hosted a father-and-son show, proud to present carvings by both Mark McNair and his older son, Ian. Moore reports that Ian's carvings sell nearly as quickly as his father's.

To hear Moore tell it, the McNair brothers are naturals at decoy carving, obviously endowed with their father's talent. Yet despite this inheritance, they were not always so certain they'd follow in their father's footsteps. After graduating from the College with a degree in history and a minor in studio art, Ian indulged his wanderlust and traveled the world for a decade. He moved to New Zealand for seven months, working on organic farms and volunteering at a national park. He taught English in Korea, spent summers in Alaska, wintered in the U.S. Virgin Islands and worked as a tour guide leading foreign tourists on cross-country road trips in the United States. For most of these adventures, Ian was joined by his wife, Rebecca Gibson McNair '03.

The globetrotter usually made room in his luggage for some tools, allowing him to continue refining his carving skills no matter where he laid down his head. Then, when Ian returned home on breaks from his travels, he would more diligently devote himself to the carving hobby he had practiced growing up. He had improved considerably since first making a carving of a perch at age 10, and had since sold a number of decoys and other carvings to collectors. But he noticed lately that each time he resumed carving, it took longer for him to return to peak performance. Ian then reached a conclusion: If he wanted to become a decoy carver on par with his father, he had to devote nearly every day to that pursuit. Forsaking his previous travel habits, Ian and his wife bought a home in Charlottesville, Va., in 2014 and began a more rooted existence. Rebecca became a schoolteacher, and Ian a professional carver.

"I realized through all my travels how important carving was to me," says Ian. "I really feel I had been given a special gift."

Colin had also carved since childhood, selling one of his first pieces to a handwriting teacher at age 6. Just as it was for Ian, Colin's affinity for carving was often a pastime squeezed in around other activities. As a boy, Colin would carve with his brother until the tide rose high enough for them to go fishing. In high school, carving stopped when wrestling season began. During summer breaks in college, Colin would work exhausting days as a mate on a fishing boat in May and June, then return to the woodshop in July for two months of carving before the fall semester began.

Colin graduated from the College with a biology degree and was inclined to begin a career devoted to the study and rehabilitation of oyster beds. But the youngest McNair received another offer too good to pass up – the chance to work for an auction house devoted to American sporting art. Since 2008, Colin has been the decoy specialist for Copley Fine Art Auctions of Boston.

Decoys are big business for Copley and other auction houses. In 2007, at the peak of the market, two decoys made by master carver A. Elmer Crowell were sold for more than $1 million a piece by Copley's parent company. These were exceptional sales, yet antique decoys still command prices that might seem inexplicable given the deteriorated condition and occasional clumsiness of the carvings.

Colin sympathizes with such confusion, understanding that the uninitiated might look at the wares he carts around in the back of a minivan and remark simply, "It's a beat-up old duck."

He politely begs to differ. Every decoy, he argues, tells a story of a particular time, place and carver, should one know how to decipher the duck.

"The whole thing is a signature," says Colin. "The hand of the maker who made it doesn't lie."

Picture Perfect

Inspiration is never far from the McNair family woodshop. Just a stone's throw from the house, the woodshop fills a quaint, barnlike building. From one workbench, one can gaze out a window at the geese roaming the garden. From another, one looks through a thin stand of cedar trees to spy the family dock and creek.

The shop is loaded with wooden stock to explore and touch. There's Northern and Atlantic white cedar from the East Coast, Alaskan yellow cedar that Ian obtained on his travels to the 49th state and big blocks of gorgeous, soft cork from Portugal. Classical music plays softly from a speaker. Complementing the clinking pianos and whinnying violins is a different type of music, one made by the friction of metal blade meeting cedar.

"The sound of a chisel against wood — it's like a little instrument," says Mark. "That's why we use hand tools. It sounds good."

To round out the sensory perfection, one just has to inhale. Like all woodshops, the McNair woodshop has a pleasant scent. Mostly it's lingering sawdust one smells and the aroma of cedar, but also faint traces of oils, paints and varnishes that have been applied over the years to hundreds of carved pieces. It is intoxicating.

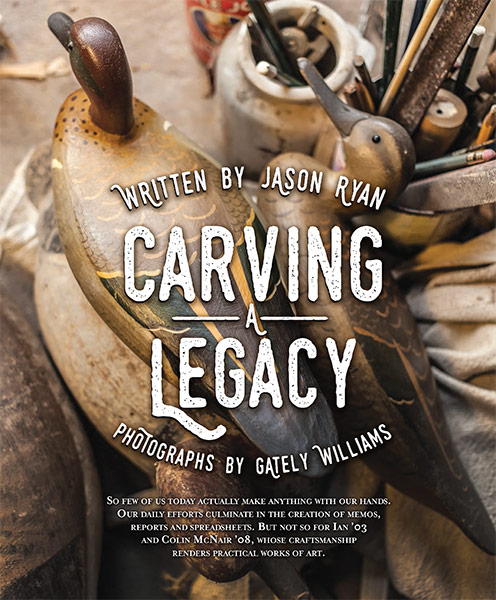

Decoy heads and bodies abound in the workshop, scattered among the tools and small cans of paint and oil. Occasionally, some of these decoy parts are picked up by one of the McNairs and refined, the decoys' lines delicately reshaped. Some heads and bodies, however, look to have sat untouched for years in the woodshop, stuffed into far corners and other out-of-reach places. Their creators had become bored or disappointed by them, judging them not worth the trouble of salvaging. Though they look perfectly good to the amateur, the McNairs' exacting eyes know different. Their eyes demand perfection.

Tools fill the shop, too, of course, many of them sharp. A few, like a vise and the bandsaw (one of the few power tools), are stationary. But most are loose, lying across workbenches, stuffed upright into cups and containers, hanging from walls and atop shelves.

When Ian opens a wide drawer in a tool chest, two or three dozen chisels are revealed. They all seem to look the same, though Ian's practiced hands know that each one behaves slightly differently. The same goes with the McNairs' hatchets. Picking one up, Ian explains it is meant for a left-handed woodworker. Only when one examines the hatchet very, very closely can it be discerned that the blade is indeed slightly beveled to one side, favoring someone who strikes down with his or her left hand.

Ian slowly draws the hatchet across his forearm, shaving it free of hair. A sharp blade, he explains, is a safe blade. Such wisdom might seem counterintuitive, but a craftsman risks less injury when his tools perform efficiently, and as expected. Paraphrasing a quote often attributed, correctly or not, to Abraham Lincoln, Ian says that if he were given six hours to chop down a tree, he'd spend the first four hours sharpening his axe.

Ian uses the hatchet to roughly chop the body of a duck from a shoebox-sized block of cedar. Assorted varieties of cedar are a favorite medium for decoy makers, as the wood is durable, light and easily detailed. Most decoys are assembled by joining a carved head to a carved body, though, after sanding and painting, it appears the decoy is made from a single piece of wood. Sometimes a piece of oak, or possibly bone, is used to make the bird's beak.

The decoy's body is often cut in half horizontally and then hollowed, to lessen its weight. Holding the decoy body firmly, Ian pushes the cedar through the revolving bandsaw blade for a smooth, straight cut down the middle. Then, he drills into the interior of each half using a wide Forstner bit, hollowing out each side of the decoy's body in rough fashion, with plans to clean this up later with hand tools.

Ian suggests that 90 percent of a decoy's cutting and carving is accomplished in a mere 10 percent of the time he ultimately spends on a piece. By this he means that he can chop and carve away large amounts of wood through heavy, broad strokes and sawcuts, transforming a rectangular block into the rough shape of a bird in relatively quick fashion. Then, as the power tools are put away, the painstaking carving work begins. Ian will progress through a set of carving tools, each one allowing for a greater level of detailing. First comes the drawknife, then the spokeshave, then a rasp or chisel, and, finally, sandpaper. With the carving finished, the decoy can be painted — another delicate and time-consuming task. With good reason does Mark McNair say, "We don't wear watches around here."

Perfection takes as long as it takes.

Close to home

Perfection is not limited to the woodshop. On a mild November morning, Ian McNair takes hold of the tiller attached to an outboard engine and begins steering through the waters around his parents' house. He and his brother have taken a quick cruise around the nearby creeks of the Chesapeake, hoping to snag a few fish on the end of a fishing line, though they enjoy no such luck. Then they tie off at the dock of a nearby crab-picking house to pick up some fresh crabmeat for dinner.

Mindful of a receding tide and the shallow waters around the family dock, they next speed home, Ian keeping a steady eye on channel markers staked throughout the creek. The water seems expansive, with plenty of room to maneuver, but the McNair men know different. Though wide, the water is very shallow, and time is running out to get the boat back home. One wrong move and the propellor might catch on the soft mud of the creek bed that is increasingly being exposed by the ebbing tide.

Concentrating intently on the few hundred yards of water that separate boat and dock, Ian navigates a serpentine path back home, tracing the narrow creek channel that is hidden underwater but imprinted on his mind. He proceeds at nearly full speed, never lessening the throttle for fear of the boat losing its plane and becoming bogged down. With each curve through the water, Ian gets the boat closer to home. Finally, Ian glides in beside the dock, with just inches, or perhaps a foot or so, of water beneath the boat. Then the McNair brothers, acting as if their arrival was never in doubt, casually tie off the boat and unload their gear.

With the tide out, there seems only one thing left to do that day. The boys skip off to the workshop, and are eventually joined by their father. Someone flips on the stereo, filling the room with classical music. Then comes a chorus of saws, rasps and chisels assaulting wood, as well as the scent of fresh cedar. Side by side the McNair men work, together carving a legacy.

For more on the McNair family's work, visit mcnairart.com.

Credits

Used with Permission. College of Charleston Magazine: Spring 2015. 44 - 53.

Read Article in PDF »