The Migratory Bird Treaty Act Centennial

Written by Rebecca Stephenson

Reprinted from the Desert Rivers Audubon Society Summer 2015 Newsletter

Billing pair by John James Audubon, from The Birds of America, 1827 - 1838. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Passenger pigeons were highly gregarious birds; flocks were frequently a mile wide and 300 miles long, taking days to pass by. The last documented colony was encountered in 1878, and by 1895, sightings of even one of the Passengery Pigeon were rare. In 1914, it was officially declared extinct.

The year is 2016, the dawn of the 21st century, and it is truly a time for the birds. Birding, as a pastime, is growing in popularity; the once-dwindling bald eagle is at record numbers; the National Audubon Society has 500 chapters scattered across the United States, and citizen scientists as well as countless researchers work to promote and conserve birds nationwide.

In this golden age of bird conservation, it is hard to imagine that it was not always this way. Few realize that many of our beloved birds were nearly driven to extinction in a particularly gruesome chapter of American history, and bringing them back from the brink was a war fraught with casualties - not all avian. It was the tireless struggle of many heroes - both sung and unsung - that resulted in the hard won piece of federal legislation that affords us the luxury of enjoying diversity among the feathered enigmas we call birds.

I am speaking, of course, of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. This landmark federal law was originally drafted in 1916, a mere four years after the Titanic's fateful voyage and Arizona’s statehood and was signed into official being in 1918, just before the conclusion of World War I. Its sole purpose was, and remains, to protect birds from people. It has stood as a stoic sentry over the birds ever since, protecting some 1,000 species with an astounding absoluteness that brooks no exception, designating it unlawful to pursue, hunt, take, capture, kill, possess, sell, purchase, barter, import, export, or transport any migratory bird, or any part, nest, or egg of any such bird, unless authorized under a permit issued by the Secretary of the Interior." It began as a treaty between the United States and Great Britain (signing on behalf of Canada) and later included Mexico, Japan, and Russia, in effect securing the well-being of nearly every native bird in North America, even after death.

The Act distinguishes between three main groups of birds: migratory game, migratory nongame, and non-native. One hundred seventy species of migratory game birds are covered, including ducks and doves, each afforded an assigned hunting season that never exceeds 3.5 months or overlaps the breeding season. Of these 170 species, only 60 are currently hunted. Birds that were historically hunted, like shorebirds, remain on the list but no longer have hunting seasons due to unsustainable population numbers. Outside of the hunting season these birds are fully protected by the Act. Migratory nongame birds include the songbirds and the majority of other North American birds and are fully protected year-around. The term "migratory" is somewhat confusing in reference to resident native birds that do not have long range migrations, but it refers to any bird that may move from place to place (thus, every bird). Non-native birds, such as the intentionally released European starling, the house sparrow, and the escaped monk parakeet, are not protected by the Act. Surprisingly, many native game birds are also unprotected, including the wild turkey.

Enforcing the Act is the responsibility of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and a wide variety of interactions with birds may be prosecuted. At present, there are very few exceptions to the Act and all require permits. These allowances include collecting birds for falconry, taxidermy, or scientific and educational use; killing or removing hazardous birds (such as geese at airports); and allowing Native Americans to harvest feathers for religious ceremonies. All other offenses, including seemingly innocuous activities like feather collection and attempting to save baby birds, are considered misdemeanors or felonies. Violators of the Act can face fines ranging from $500 to $2,000 as well as jail time anywhere from six months to two years, with charges that may be stacked and accrued per affected bird. The Act, in addition to being thorough, is severe. But how does a law with such sharp teeth come to be deemed necessary? The answer is a long, grisly lesson in American history, peppered with tragedy.

In the early 1800s, while John James Audubon was chronicling North American birds for his now-famous Birds of America, birds were viewed as a bottomless economic commodity. Audubon himself frequently described the palatability of birds in the same clinical manner as he did their plumage color and behavior. Dark-eyed juncos, for example, had "flesh extremely delicate and juicy," and even American robins were harvested by the thousands, their meat sold in city markets. It was a plentiful new world, and Americans freely picked its fruits. Although somewhat forgivable in the face of such unfathomable abundance, nothing more clearly demonstrates the results of this obliviousness than the demise of the passenger pigeon.

Earliest published illustration of the Passenger Pigeon (a male), Mark Catesby, 1731. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In his famous account from 1813, Audubon observed a flock that flew overhead for three consecutive days, writing, "The light of the noonday sun was obscured as by an eclipse." Passenger pigeons were highly gregarious birds; flocks were frequently a mile wide and 300 miles long, taking days to pass by. No bird in the world, past or present, can rival the magnitude of their population, estimated at three to five billion when Europeans first arrived in North America. At these numbers, passenger pigeons easily accounted for a quarter of all birds on the continent at the time. To put this in perspective, the red-winged blackbird, currently one of the most numerous birds in North America, boasts a population of only 160 million birds.

In addition, flocks would gather to feed on tree mast and to breed, giving an overall impression of infinitude to on-looking Americans. Pigeon meat became a staple for the poor and was used as food for slaves. Market hunters quickly capitalized on a copious source of easy money, and entire flocks were decimated at nesting sites by gunshot, felling trees to dislodge chicks, poisoning with sulfur smoke and netting. With the advent of better killing, shipping, and storage technology, harvest became larger and larger. In 1857, a group of bird preservationists in Ohio grew concerned over the 300-ton reaps frequently taken and proposed a bill to protect the bird, but the state senate denied it, declaring that the passenger pigeon needed no protecting, being "wonderfully prolific." Yet, the last documented colony was encountered in 1878, and by 1895, sightings of even one of the birds were rare. In 1914, it was officially declared extinct.

Carolina parakeets by John James Audubon (1833). Source: Wikimedia Commons

The extreme social nature of this bird proved to be part of its undoing, illustrating naturalist Paul R. Ehrlich's point that "it is not always necessary to kill the last pair of a species to force it to extinction." It has since been realized that the birds required large flocks to breed, and scattered isolated remnants were unable to sustain the species. Yet, it would take more than annihilating the most numerous birds on Earth to teach this lesson. While the passenger pigeon was being harvested en masse for profit, another iconic North American bird, the Carolina parakeet, was systematically being removed due to its agricultural nuisance. Farmers would shoot the birds, which fed on fruit crops, but the birds would behave fearlessly in response, demonstrating what Audubon described in 1842 as a "fatal habit of hovering over their fallen companions." More and more birds would gather to aid the slain, volunteering themselves to be slaughtered by the score. By 1860, this species was rare, and in the early 1920s, North America's only native parrot joined the passenger pigeon in extinction.

The need for food and the defense of crops were somewhat understandable reasons to kill birds, but another reason emerged in 1870: fashion. The affluence of the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, and millinery (hat-making) became a 17 -million-dollar per-year industry. With milliners always searching for new, colorful materials to adorn their creations, it wasn't long before the trade's collective eye landed on one of nature's finest constructions: bird feathers. As famed conservationist Aldo Leopold states, "Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty." Never was this statement more true than with the plume-hunting craze.

In 1886, ornithologist Frank Chapman went birding on the streets of New York City. That is, he was able to identify 64 species of birds in 15 different genera on the hats of well-to-do ladies, none of them by sound. The feathers, and sometimes entire stuffed bodies, of smaller birds including sparrows, warblers, bluebirds, and woodpeckers were used as decor on the hats, with the longer plumes and aigrettes of larger birds such as egrets and herons adding still more flair.

A plume covered hat.

Between 1886 and 1900, more than five million birds per year were killed in the name of fashion, with Florida's water birds, specifically egrets, taking the brunt of it. The demand was worldwide, and feathers from birds in the Everglades made it as far as London and Paris. The white breeding plumes of the snowy egret were particularly prized, and the fact that the birds were abundant and approachable made the "little snowies" prime targets. In the height of the craze, plumes were valued at $32 per ounce - the same as the price of gold at the time-and plume hunters flocked to the Florida Everglades in droves to reap the bounty. As feathers are relatively lightweight, the plumes of four birds were required to make one ounce. These calculations become more devastating when the life history of the birds is considered: Egrets grow plumes only during their breeding season, meaning the slaughter of so many adults left even more eggs and young abandoned. One former plume hunter proclaimed, "The heads and necks of the young birds were hanging out of the nests by the hundreds. I am done with bird hunting forever!"

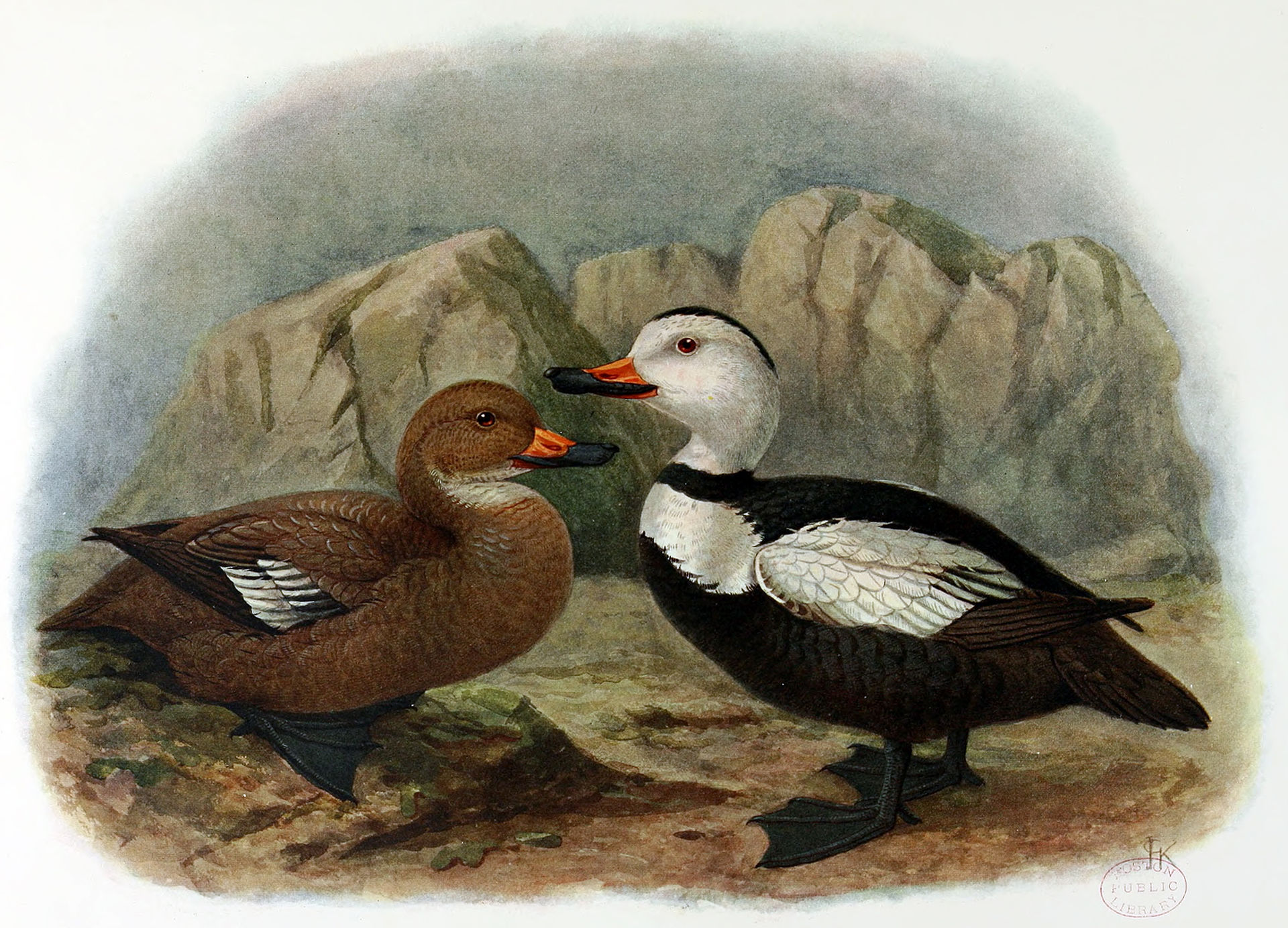

Illustration by John Gerrard Keulemans of a female and male Labrador Duck. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the face of four significant extinctions (the Labrador duck and Eskimo curlew joined the passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet in the late 1800s) and the loss of 95 percent of Florida's water birds to the plume trade, bird conservationists began taking serious action. The American Ornithologist's Union, formed in 1883, proposed a Model Law for bird preservation in 1886, and socialite Harriet Hemenway formed the Massachusetts Audubon Society in 1896, proving integral in urging women to decry the plume industry. Hemenway exposed the popular fallacy that plume hunters were taking naturally molted feathers. In 1899, Audubon magazine urged conservation and tried to raise awareness. This culminated in the Lacey Act of 1900, which forbade the selling of poached birds, or bird parts, in different states than they were harvested. This was the first of many small legislative successes for conservation.

In 1901, Theodore Roosevelt was elected president and the bird conservation movement saw further success and a series of significant "firsts." The American Ornithologist's Union hired Guy Bradley, a former plume hunter, as the first wildlife warden of the Everglades. To attempt to save egrets from certain extinction, Roosevelt declared Florida's Pelican Island a protected area by executive order in 1903, in so doing establishing the first national wildlife refuge. Guy Bradley bravely patrolled the treacherous terrain of the Florida backwoods for three years, apprehending plume hunters as necessary to defend the birds. He was murdered during one such confrontation in 1905. The 35-year-old's obituary reads:

Hand-colored lithograph of Eskimo curlews from A History of the Birds of Europe (1871-1881) by Henry Eeles Dresser (1838-1915). Source: Wikimedia Commons

"Heretofore, the price has been the life of birds, now is added human blood. Every great movement must have its martyrs, and Guy M. Bradley is the first martyr in bird protection." Two more wardens were murdered and both the snowy and great egrets were nearly extinct when the Audubon Plumage Act was passed in 1910, banning the sale of plumes and finally ending the destructive craze.

These events ultimately led to the more formidable Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which, bolstered by the grievous extermination of the passenger pigeon and the significant losses of the plume trade, sought to prevent such atrocities from ever occurring again. The act has been a massive success, mitigating the excessive, unsustainable exploitation by establishing hunting seasons to regulate the killing of birds necessary for food and sport, ending destructive egg and feather collecting, and banning the killing of native, nongame species altogether. Although it was implemented too late to save the passenger pigeon or Carolina parakeet, the act and the conservation law trend it began succeeded in bringing the egrets back from the brink of extinction. The great egret became the poster child for the National Audubon Society, and the Act continues to ensure the safety of the great many birds we enjoy today. It is imperative, now more than ever, that Americans allow this noble sentinel to remain on duty.

Credits

Used with Permission. Written by Rebecca Stephenson and Reprinted from the Desert Rivers Audubon Society Summer 2015 Newsletter.