Decoys of Substance and Desire

Essayist William Reeve usually writes here about furniture. This time, however, he and Bernie Gates capture the essence of decoys: their history, their creation and their collectability.

by Bernie Gates & William Reeve

1 Lovelock Cave canvasback.

One could argue that, after the human body, the most frequently sculpted form has been the duck, especially during the last two centuries. In his 1753 publication The Analysis of Beauty, William Hogarth (1697-1764) singled out what he designated “the line of beauty” (48), the ogee or cyma curve best illustrated on the cabriole leg of a Queen Anne chair. Part of the aesthetic appeal of the duck may lie in its basic body shape which potentially projects no less than five of these “s”- shaped curves: the breast, the tip of the bill to the crown of the head, the crown to the base of the hindneck, the back and below the tail. To this day, if one enters a craft shop or a china store, one can be almost certain to find on display examples of wildfowl in wood, porcelain and other mediums.

Ducks are by nature curious and of an exceptionally gregarious nature. Because they tend to gather in flocks, their predictable behaviour renders them an easy prey for the hunter to lure into range. We know from wall paintings that the ancient Egyptians exploited these ingrained tendencies by using live ducks as decoys.

The word decoy from the Dutch "de kooi," meaning the cage, derives from the 17th-century Dutch practice, subsequently imported to England, of driving unsuspecting wildfowl into an immense cage that narrowed into a tunnel from which there was no escape. It amounted to a more systematic approach to the old method of beating or scaring game into a focused corral in which it could be shot.

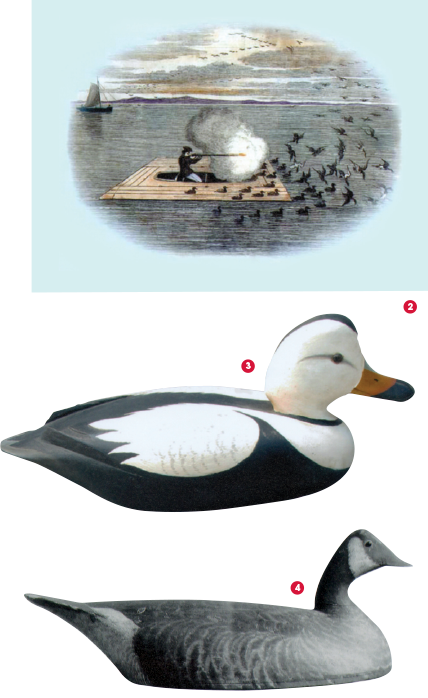

2 Sinkbox.

3 D.W. Nichol Labrador duck, now extinct.

4 George Warin Canada goose.

Before the arrival of Europeans in North America, the native peoples had recourse to decoys to harvest the vast flocks of birds that migrated annually across the continent. In 1928 archaeologists discovered eleven amazingly well preserved examples, more than a thousand years old, in the Lovelock Cave of Nevada (plate 1). Aborigines had bound reeds together and covered them in birdskin and feathers to suggest the shape of canvasbacks. They even carried their original anchor tethers. When English settlers arrived on the East Coast of America at the beginning of the 17th century, many did not survive their first winter, dying of starvation. The ones who did prevail owed their lives in part to the First Nations, for they came to the rescue of the white men in their fledgling colonies, teaching them how to hunt ducks by baiting them into shooting distance with makeshift floating decoys. It was only a matter of time before Europeans began to improve upon this procedure by carving their lures out of more durable and reusable wood.

In the early colonial years there was no shortage of this abundant supply of food since amazing flocks of wildfowl literally darkened the sky with their sheer numbers as they migrated each Spring and Fall. Hunting was therefore first and foremost a means of survival, a welcomed method to supplement one’s diet. In the best democratic tradition of the New World, it was practiced by all, regardless of class, whereas in Europe hunting had always been the exclusive preserve of the upper class and poaching could be punishable by death. In the last half of the 19th century, what has been called "the greatest hunt in the history of the world" (Ridges 21) took place in North America. After the breach-loading rifle replaced the muzzleloader, hunting became a more efficient alternative to earn one’s living, especially during the boom years of an ever-expanding American economy. High-class hotels and restaurants in major urban centres such as New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Toronto and Montréal clamoured for wildfowl to meet the demands of their wealthy clientele. In addition, the recently constructed railways made it possible to deliver the kill while it was still relatively fresh. We now refer to this era as the market hunting period, when professional hunters with rigs of up to 200 to 300 decoys slaughtered thousands upon thousands of birds. On a good day some of these market hunters, largely farmers, fishermen, or boat builders in the off season, would harvest close to a thousand ducks, each employing as many as three shotguns, exchanging them when they became literally too hot to handle, or a four-bore shotgun called a “sinkbox cannon” capable of downing a hundred birds with one discharge. Some resorted to a “sinkbox” (plate 2), a boat with wide gunnels on which they placed heavy metal weights, occasionally in the shape of ducks, to keep the box section low in the water. The hunter would crouch down in the box of the boat anchored in the midst of his decoys and rise at the appropriate moment to take his toll of ducks. It was often dangerous since high waves could easily swamp this low-riding craft. Hunters also built permanent blinds on shore in the marshes near their lures, or they “screened” for ducks. In the latter scenario, they would set out their decoys about 200 feet from shore and once the ducks landed among them, they would stealthily scull their screening boat, from whose bow rose a suitably camouflaged blind, towards the unsuspecting flock. The efficiency and sheer volume resulting from these hunting practices led to the eventual extinction of some species, notably the Labrador duck (plate 3) and one of the most common North American species, the passenger pigeon. In response to this carnage, the governments of Canada and the United States cooperated in drawing up the Migratory Bird Conservation Act in 1916 to place serious limitations on waterfowl hunting. It became law in Canada in 1917 and the following year in the States. Ducks, geese and shore birds could no longer be sold and private hunters had to adhere to a bag limit during a short Fall season.

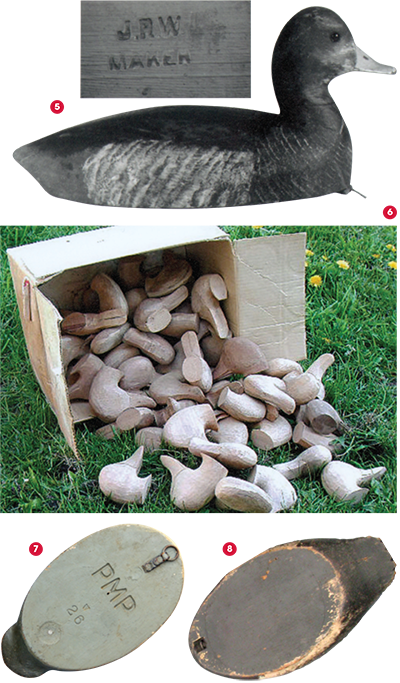

5 John R. Wells bluebill drake. Insert shows maker's brand.

6 Box full of D.W. Nichol heads.

7 Bottom showing inset weight, number, W (whistler), PMP (maker), plug, leather strap and metal ring.

8 Inlet bottom board and recessed staple for anchor tether line.

During the market hunting years, hunters either made their own decoys in the off season or purchased their needs from well-known carvers in their respective region. The end of the era spelled disaster for many of the full-time professional carvers but some were able to adapt, since they were also boat builders and sport hunting did survive. Even before the Act, wealthy men formed clubs such as the St. Clair Flats Shooting Company or the Long Point Shooting Club, hired guides who provided the decoys and indulged in a week or weekend of hunting. In this context it is worth noting that the Duke of York, the future King George V, enjoyed two days of duck hunting in Manitoba’s Delta Marsh, arranged by the Toronto boat builder and carver George Warin, in 1901 (plate 4). The party of five bagged 600 ducks. Furthermore, his son Edward, during a 1919 royal tour, went duck hunting in both Manitoba and Ontario using 300 decoys made by John Wells of Toronto (plate 5; cf. Fleming 156-57).

The duck decoy is now recognized and appreciated as one of the most important manifestations of that elusive, difficult-to-define entity known as folk art. It did derive from local, popular sources and represents the ideal combination of the utilitarian – it had to stand up to the rough treatment of the annual hunt – and the aesthetic – it had to be sufficiently attractive to lure the prey into range. Although ducks are not especially fastidious and can be decoyed with a mere pile of stones, some carvers felt that certain species, above all the black, required a particularly true-to-life wooden representation to be successfully enticed into range. Hence there exists a wide range of decoy interpretations depending upon, among other factors, the basic form of the duck in question, the interpretive eye and mind of the individual carver and the regional demands made by the specific hunting grounds.

The basic duck decoy consists of two parts: the head carved from pine, basswood or willow and the body fashioned of white cedar, pine or basswood. The parts are first roughly shaped with a saw, axe, drawknife, or spokeshave and the finer details often added simply by means of a penknife. Davey Nichol, for example, whittled boxes full of heads (plate 6) in preparation for later assembly with a stored-up collection of seasoned bodies. Glue and a screw through the bottom of the block, the metal screw head concealed by a plug, attach the two parts. The bottom (plate 7) customarily carries a weight near the tail end to offset the load of the head at the front and to ensure that the decoy floated evenly and looked natural. This weight can consist of part of a horseshoe, a butt hinge or a lead disk shaped by being poured into a pocket-watch case. As well, at the front end of the bottom, one invariably finds a leather strap holding a metal ring or a staple either projecting beyond the surface or set into a cavity to avoid fouling the tether lines attached to the ring or staple. Some decoys also bear a wooden or metal keel, permanently attached or removable, contrived to keep the decoy upright in turbulent water conditions.

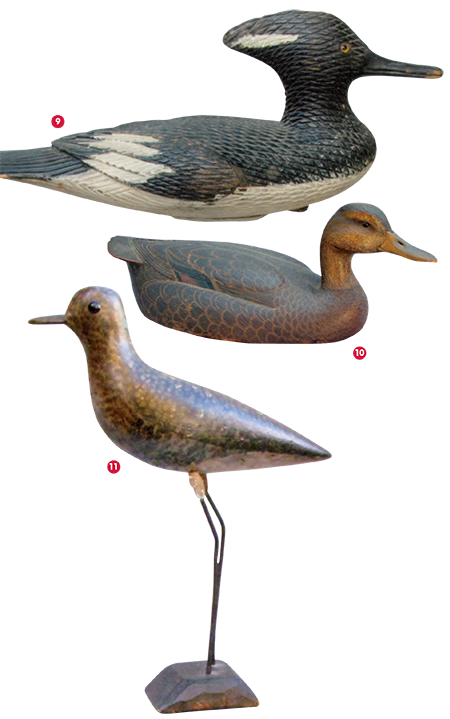

9 Female hooded merganser

attributed to Sam Hutchings.

10 Peter Pringle "super" black.

11 Golden plover Toronto

Harbour shorebird.

The body itself may be either solid or hollow. In the latter case, two methods were utilized. A single board, often sawn from the bottom of the block, is later reattached with glue, nails and/ or screws once the remaining body has been hollowed out (see plate 13), sometimes to a remarkably thin shell weighing next to nothing. In the second, more demanding approach, an inlet bottom would be set into the hollowed-out block to rest level with the lower edges of the sides (plate 8). The bottom may be stamped or painted with a name or initials. These indicate either the maker or more frequently the owner. Since sportsmen often set out their decoys together with those of their fellow hunters to increase the size of the rig, their initials would enable them to distinguish and collect their own birds at the conclusion of the hunt. Whereas decoy carvers rarely autographed their work (see plates 5 and 7), usually the style of the decoy is as good as a signature. Although makers tended to copy the example of the dominant, recognized expert of the region or the patterns of their father or grandfather, carvers would never fashion their decoys in exactly the same way. After the body had been suitably seasoned, it was usually covered in a primer or sealer such as linseed oil or lead paint to help waterproof the wood. The decoration in ordinary house or boat paint and occasionally even in artistic oils could be quite basic but with the more artistically inclined, it could also be quite detailed and verisimilar.

Environmental considerations largely determined the size of decoys. In potentially choppy expanses of water such as the St. Lawrence River, Lake Ontario or Lake Erie, birds had to be bigger both to be seen and to withstand the severe conditions of open water, while smaller decoys proved more effective and more practical for inland rivers, lakes and marshes. Decoys may be roughly divided into two essential orientations: the impressionistic versus the realistic. Most hunters just wanted good, solid, dependable lures that would stand up to the rigorous Fall weather conditions and the rough treatment of the hunt. They also had to be sufficiently light and compact so that several dozen could be carried over the shoulder in a burlap sack. Some decoy carvers, however, took particular pride in their work and were gifted with an artistic talent revealing itself in the creation of some of the finest examples of folk art, a coalescence of the aesthetic and the utilitarian in a beautiful tool. These men went the extra mile with unnecessarily carved and/ or rasped surfaces, elegantly sculptured forms and exquisitely painted details. In the Canadian context an illustration of the impressionistic style at its best would be the small hooded mergansers attributed to Sam Hutchings with their cross-hatched bodies to cut down the glare (plate 9). The realistic trend finds its most devoted practitioner in Peter M. Pringle who took no less than three years to perfect two hollow black ducks almost to the degree of refinement we now associate with the decorative, non-working mantle bird (plate 10).

12 Widgeon hen and an early bluebill hen by LeBoeuf.

13 A Bob Jones redhead in untouched condition after years of service. Shingle-board bottom.

14 Addie Nichol bluebill hen.

Shorebirds constitute another specialized category for some carvers, one that was particularly popular in the United States and to a lesser degree in Canada. The typical shorebird lure is also composed of essentially two parts: the body and head fashioned out of one piece of wood and a long, narrow, usually wooden bill inserted into the head (plate 11). These carvings would stand on one or two legs made of wire or wood that could be driven into the ground near a body of water. Because these shorebirds are relatively rare and often display a stunning sculptural beauty, they are much sought after by collectors both of decoys and folk art.

Decoys display a remarkable distinctiveness and unique assessment of each species by each carver. No two decoys are ever exactly alike and the birds of each carver differ noticeably from the interpretations of their fellow artists even if they lived in close proximity. However, distinctive regional characteristics do emerge, primarily as a result of geographical features such as inland versus Great Lakes. Moreover, it was often the case that one local maker gained substantial notoriety and recognition to the extent that he influenced the carving and/ or painting style of those residing nearby who sought to emulate his success. As a consequence, we can now speak confidently of several schools of decoy carvers whose work shared many characteristics in a specifically defined region.

Decoys were made in all the provinces of Canada but especially in Ontario, Québec and the Maritimes, provinces served by two migratory routes, the Atlantic and the Mississippi flyways. Whereas both the Maritimes and Québec can boast of some truly outstanding carvers such as Amateur Savoie, Oscar Crowell, Orel LeBoeuf (plate 12) or Bill Cooper, Ontario has produced the most celebrated carvers and schools. To mention a few, the Toronto School is known for the light, smooth, well-proportioned, hollow birds of George Warin (see plate 4), Tom Chambers or John Wells (see plate 5) while the Dunnville School created the skillfully rasped, realistically painted decoys of Peter Pringle (see plate 10) and Ken Anger. In Prince Edward County, we have the “County” birds, the “fine, hollow construction and [the] unique” lures (Stewart 7) of Bill Crysler, Angus Lake or Bob Jones (plate 13). Other areas of interest include Western Ontario, Hamilton Bay, Whitby/ Oshawa, Peterborough and the Thousand Islands. For residents of the Brockville/ Kingston/Napanee region, the dominant influence in the first half of the 20th century has been the Nichol family responsible for establishing a style recognized throughout North America as belonging to the Smiths Falls School (plate 14).

Works Cited

1. Fleming, Patricia (ed). Traditions in Wood. Camden East, ON: Camden House, 1987. 2. Gates, Bernie. Ontario Decoys II. Kingston, ON: The Upper Canadian, 1986. 3. Ridges, Bob. The Decoy Duck. Limpsfield, Surrey: Dragon’s World, 1988. 4. Stewart, Jim. The County Decoys. Erin, ON: Boston Mills, 2004.

Used with Permission 2Brilliant Media Inc. — Canadian Antique & Vintage: Since 1963, the Authoritative Voice of Canadian Antiques, Folk Art & Fine Art, and Vintage Collectibles, JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2015.

Read Article in PDF »